How Do These Animals Attract a Mate?

Love is in the air—and underwater—at Greater Cleveland Aquarium. With Valentine’s Day this week, you might be wondering how certain species at the Aquarium attract mates. Read on for a few fun animal courtship facts, from horseshoe crabs to red-bellied piranhas.

Weedy Seadragons

///

Solomon Island Leaf Frog

///

Red-Bellied Piranha

///

Red-Eared Slider

///

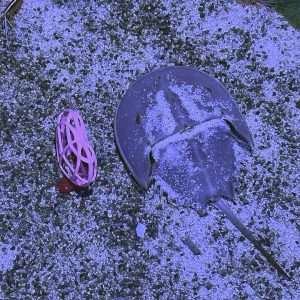

Horseshoe Crab

///

Plan a visit to Greater Cleveland Aquarium to learn more about species and nearly 250 others. We’d love to “sea” you!

For more Valentine’s Day animal fun facts, check out the playlist below:

Shovelnose Sturgeon – Check out that shovel-shaped snout.

Shovelnose Sturgeon – Check out that shovel-shaped snout. Red-eared Slider – This turtle is named for the red patch on its ear AND the way it slides into the water when startled.

Red-eared Slider – This turtle is named for the red patch on its ear AND the way it slides into the water when startled. Clown Knifefish – This fish’s knife-like shape allows it to swim both forwards and backwards.

Clown Knifefish – This fish’s knife-like shape allows it to swim both forwards and backwards. Crystal-eyed Catfish – Frank Sinatra might have been “ol’ blue eyes,” but this catfish gets attention for its light blue peepers.

Crystal-eyed Catfish – Frank Sinatra might have been “ol’ blue eyes,” but this catfish gets attention for its light blue peepers. Dyeing Poison Dart Frog – This name comes from an unverified legend that indigenous people used these colorful frogs to dye parrot feathers.

Dyeing Poison Dart Frog – This name comes from an unverified legend that indigenous people used these colorful frogs to dye parrot feathers. Picasso Triggerfish – This peculiar-looking fish has bright, artsy colors AND a dorsal spine will raise when startled.

Picasso Triggerfish – This peculiar-looking fish has bright, artsy colors AND a dorsal spine will raise when startled. Hammer Coral – Note the hammer shape of these coral polyps.

Hammer Coral – Note the hammer shape of these coral polyps. Scrawled Cowfish – The “horns” above its eyes and irregular body markings are what give the scrawled cowfish a distinctive appearance.

Scrawled Cowfish – The “horns” above its eyes and irregular body markings are what give the scrawled cowfish a distinctive appearance. Raccoon Butterflyfish – This butterflyfish is named for the black-and-white “mask” around its eyes.

Raccoon Butterflyfish – This butterflyfish is named for the black-and-white “mask” around its eyes. Black Drum – This fish can make drumming or croaking sounds with muscle movement around its swim bladder.

Black Drum – This fish can make drumming or croaking sounds with muscle movement around its swim bladder.